There are few certainties in a general election campaign. This time is no different, though there are two things of which we can be reasonably confident.

First, the UK’s parlous fiscal position will hang over the campaign like a dark cloud. Both Labour and the Conservatives are committed to precisely the same debt target. That target is currently on track to be met by the finest of margins. Promises of fiscal largesse, whether tax cuts or spending increases, would mean breaching it. If the parties are serious about their fiscal rules, they’ll have to keep a lid on those promises.

Second, the parties will do everything possible to avoid revealing how they’d approach the difficult economic and fiscal trade-offs awaiting the next government in the autumn.

Here, we discuss each of these points in turn before reflecting on what they mean for the campaign.

Why it’s so hard to get debt falling

Jeremy Hunt and Rachel Reeves, and their respective parties, have both committed to have debt as a share of national income (the debt-to-GDP ratio) falling by the fifth and final year of the forecast. Both have other fiscal targets, but it is this debt rule that is currently acting as the binding constraint. The problem is, for a Chancellor with a goal of reducing debt as a fraction of national income, things have arguably never been so bad.

Government debt is measured relative to the cash size of the economy – what fiscal nerds refer to as nominal GDP. This is the denominator in the debt-to-GDP ratio. When the cash size of the economy is growing quickly – due to either high inflation or rapid ‘real’ economic growth – it is, all else equal, easier to get debt falling. It’s also easier to get debt falling when interest rates are low, and indeed when debt is low, because the government doesn’t need to spend as much on servicing its debt. When one or both of those conditions are satisfied, the government can run looser fiscal policy – it can borrow more – without pushing debt onto a rising path.

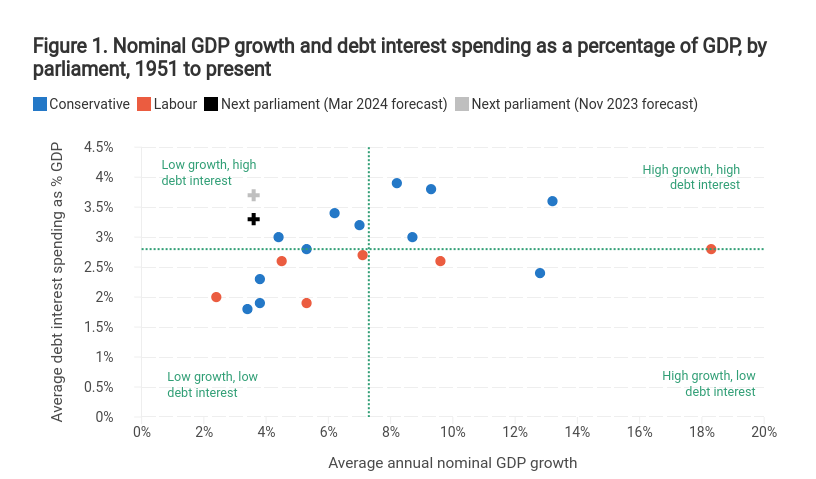

The trouble is, neither of these conditions – high growth or low debt interest payments – are expected to be satisfied in the next parliament. In fact, the latest official forecasts that the next government will face lower than average nominal GDP growth (3.6% per year) and higher than average debt interest spending (3.3% of GDP): the worst of both worlds. This is summarised in Figure 1 and explained in more detail in this previous election briefing.

This picture improved slightly between November 2023 and March 2024 (as shown by the difference between the black and grey markers in Figure 1) as forecasts for debt interest payments came down slightly. These forecasts are subject to considerable uncertainty and it is entirely possible that things will improve further. Growth could pick up, or debt interest payments could fall. The combination of weak growth and high interest rates would certainly be unfortunate and unusual historically, and we may get lucky.

But we might not. Just because thousands of English and Scottish football fans are crossing their fingers and hoping for the best this summer doesn’t mean that the next Cabinet should do the same. The fiscal outlook might even have deteriorated since the spring, as central banks have indicated that they intend to keep interest rates higher for longer, and the scale of the bill for various compensation schemes (most notably to victims of the infected blood scandal) has become apparent. Indeed, some reports suggest that one reason we’re having a summer election is that the government didn’t expect to be able to cut taxes in an autumn statement without breaching its promise to get debt falling. This debt target leaves a lot to be desired in terms of its design, but that is almost beside the point. Whoever presides over the post-election fiscal event is likely to have very limited fiscal room for manoeuvre.

Inevitable post-election trade-offs

This limited room for manoeuvre – limited “headroom” in the oft-used but rather unhelpful parlance – will be despite a considerable package of tax rises and spending cuts built into the baseline. Taxes as a share of national income are forecast to grow from 36.5% of national income in 2024–25 to 37.1% in 2028–29, not least due to an ongoing freeze to the cash value of income tax thresholds (a freeze which has another three years to run). Spending on everything other than debt interest is set to fall from 40.8% to 39.0% of national income. The fact that this is only just enough to stabilise debt in five years’ time speaks to the difficulty of the economic and fiscal inheritance awaiting the next government.

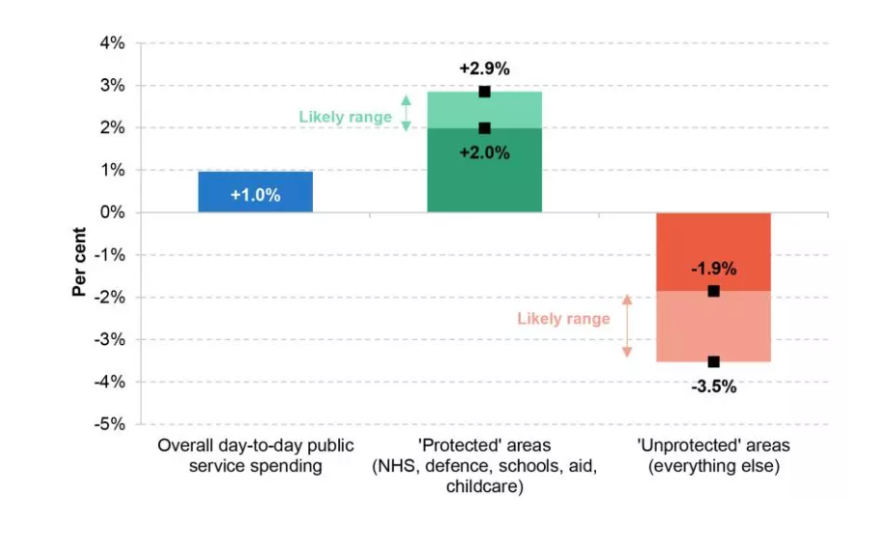

On the spending side, one major and fairly immediate challenge for the next government will be the Spending Review due by the end of the calendar year. Departments do not have detailed budget allocations beyond this year (2024–25). The high-level spending plans published alongside the March Budget, which will act as the baseline for the parties’ election promises and be the starting point for the next government, imply cuts to some ‘unprotected’ budgets. Precisely how big those cuts are depends on what happens to the ‘protected’ areas (like health and defence), among other things. The whole point is, there are no published plans beyond this year, meaning that we don’t know. A reasonable estimate is that unprotected budgets face cuts of between 1.9% and 3.5% per year (or between £10 and £20 billion by 2028–29) – see Figure 2. Notably, this is before accounting for recent announced increases in defence spending. The precise figures are less important than the fact that there are cuts on the way with absolutely zero sense from the main parties about where those might fall.

Figure 2. Estimated change in day-to-day departmental budgets (average annual real-terms growth) under existing spending plans, 2024–25 to 2028–29

Investment budgets, too, are facing cuts. Government investment is set to fall sharply as a share of national income even with Labour’s promise of an additional £23.7 billion of green investment over the parliament.

It’s not that spending cuts would be impossible to deliver. It’s that they would be impossible to deliver while maintaining the existing contours of the welfare state (even before the planned expansion of childcare subsidies and introduction of a lifetime cap on social care costs), and while maintaining the current range and quality of public services. We could, as a country, decide to charge for services that are currently free, or to means-test things that are currently provided universally, or for the state to stop doing things that it currently does. Yet such discussions seem unlikely to feature in the debate. We wouldn’t allow parties to tell us they will raise taxes without specifying where from, yet we allow them to promise spending cuts without any detail as to where the axe will fall.

The winners of the election won’t be able to dodge this question for long. The next government may choose to hold a one-year Spending Review (covering just 2025–26) to give itself more time to plan its strategy and come up with a coherent plan for the rest of the parliament. This would delay, but not fundamentally alter, the trade-offs required.

Readers can explore these trade-offs for themselves using our interactive ‘Be the Chancellor’ tool, produced in partnership with Nesta.

What this means for the campaign

If we look at the big fiscal picture, the next government effectively has three options. It can implement the spending cuts baked into existing plans – cuts that will inevitably be painful. It can implement tax rises – over and above those already in the books. Or it can borrow more – something that is highly unlikely to be consistent with a promise to stabilise debt as a share of national income. The parties might well be reluctant to tell us which of these they would opt for upon taking office. That doesn’t mean that we should refrain from asking them.

It is perfectly possible to make a principled case for each of these options. It is perfectly reasonable to hope for more economic growth, and highly desirable for parties to present plans for how they’d aim to deliver it. But there is no escaping the tough fiscal realities facing the UK. For a party to enter office and then declare that things are ‘worse than expected’ would be fundamentally dishonest. The next government doesn’t need to enter office to ‘open the books’; those books are transparently published and available for all to inspect. We should use them as the basis for an open and robust discussion during the election campaign.

[See original article for explanation of figure data sources, assumptions and caveats]