Martin Shaw will report tomorrow

Martin Shaw will report tomorrow

The UK is likely to have a general election next year, prime minister Rishi Sunak has hinted.

Jane Dalton www.independent.co.uk

It’s the first time the PM has hinted at a possible date as speculation has been mounting on whether he would call one before being forced to as Labour surges ahead in the polls.

The last time the country voted in a general election was on 12 December 2019 and the new Parliament then met on 17 December.

The next general election must be held within five years of that date, so it would need to be before 17 December 2024, although a prime minister is free to call one at any time.

If an election has not been called before then, Parliament would be automatically dissolved and the election would take place 25 working days later, according to the Institute for Government.

This means the latest possible date for the next general election would be 28 January 2025.

Mr Sunak’s hint about the date came as he interviewed tech billionaire Elon Musk at the UK summit on the safety of artificial intelligence at Bletchley Park.

The pair discussed AI’s future impact on jobs, the economy and even friendships. The prime minister then went on to sat it was vital to tackle fake news, given that there were several national elections around the world next year.

He added: “Probably here.”

In February, Conservative Party chairman Greg Hands said: “The next 18 months will see us win or lose the next general election,” – which was seen as a hint that Mr Sunak could go to the country in September next year.

Mr Hands said the “strong expectation would be 2024” and a vote in January 2025 would “not be very festive” because parties would have to campaign over Christmas.

After Labour overturned large Tory majorities in Mid Bedfordshire and Tamworth in October, winning both by-elections, the Conservatives are thought to be planning to leave the nationwide poll late in the hope of an upturn in fortunes.

Residents living in Seaton in East Devon have endured a day to forget after they awoke to find sea water had breached the town’s defences. Water flooded the streets and video captured earlier today shows how the seaside town was transformed into a mini-river.

Elliot Ball www.devonlive.com

It was a similar picture across Devon and other parts of the UK as Storm Ciaran brought down torrential rain and strong winds. However, it appeared as though Seaton suffered more than most.

The worst of the weather began when Trevelyan Road, a residential street running off the seafront Esplanade began to flood. Homeowners described water coming over the sea wall at about 8.30am.

Damage was also caused to a cafe on the seafront. The owners of the Hideaway have posted details on Facebook They said: “The Hideaway has sustained damage from Storm Ciaran. The storm door and front doors have been pushed in and water has come all through the restaurant.

“We will be closed until we can repair and make our cafe safe again. Please DO NOT come down to look in as it’s still very dangerous. We will keep everyone posted with news as much as possible.”

Speechless – Owl

Former health secretary Matt Hancock told officials that he – rather than the medical profession – “should ultimately decide who should live or die” if the NHS was overwhelmed during the pandemic, the Covid inquiry heard.

Aletha Adu www.theguardian.com

“Fortunately this horrible dilemma never crystalised,” the former head of the NHS, Lord Simon Stevens, said in his evidence to the inquiry on Thursday.

Stevens, who led NHS England until 2021, said he stressed at the time that no individual secretary of state should be able to decide how care was provided, “other than in the most exceptional circumstances”.

Hancock’s position, which materialised during a planning exercise at the Cabinet Office in February 2020, was a different one from his predecessor, Jeremy Hunt, who had wanted such decisions to be reserved for clinical staff.

Stevens told the inquiry that this ethical question was never resolved and cropped up again during the pandemic when “rationing” of NHS services was discussed.

The former NHS chief was largely uncritical of Hancock, unlike other figures who appeared before Heather Hallett’s inquiry this week, including former No 10 senior adviser Dominic Cummings and ex-civil servant Helen MacNamara.

Stevens’ witness statement referred to the “Operation Nimbus” planning exercise, which he said was helpful in terms of outlining the pressures government departments might have faced.

“It did however result in – to my mind at least – an unresolved but fundamental ethical debate about a scenario in which a rising number of Covid-19 patients overwhelmed the ability of hospitals to look after them and other non-Covid-19 patients,” he said.

“The secretary of state for health and social care took the position that in this situation he – rather than, say, the medical profession or the public – should ultimately decide who should live and who should die.”

On the final day of evidence this week, the inquiry saw new details of Johnson’s witness statement, in which he expressed his frustrations with the NHS, blaming the health service for the first lockdown.

The former prime minister blamed “bedblocking” in the NHS for locking down the country as Covid took hold.

He said: “It was very frustrating to think that we were being forced to extreme measures to lock down the country and protect the NHS – because the NHS and social services had failed to grip the decades-old problem of delayed discharges, commonly known as bedblocking.

“Before the pandemic began I was doing regular tours of hospitals and finding that about 30% of patients did not strictly need to be in acute sector beds.”

Stevens rejected Johnson’s claims, noting the sheer number of coronavirus patients needing a hospital bed was far higher than the number of beds that could have been freed up.

“We, and indeed he, were being told that if action was not taken on reducing the spread of coronavirus, there wouldn’t be 30,000 hospital inpatients, there would be maybe 200,000 or 800,000 hospital inpatients,” Stevens told the inquiry.

“Even if all of those 30,000 beds were freed up – for every one coronavirus patient who was then admitted to that bed, there would be another five patients who needed that care but weren’t able to get it,” he added.

While Stevens declined to criticise Hancock when giving evidence, the inquiry heard that Cummings had repeatedly pushed Johnson to sack his health secretary because he had “lied his way through this and killed people and dozens and dozens of people have seen it”.

In one message, Cummings complained about Stevens and Hancock “bullshitting again”.

Stevens was shown messages, but said: “There were occasional moments of tension and flashpoints, which are probably inevitable during the course of a 15-month pandemic, but I was brought up always to look to the best in people.”

Appearing later, the top civil servant in the Department of Health, Sir Christopher Wormald, said that Hancock would probably be surprised by how “widespread” the perception was regarding his frequency of alleged “untruths”.

Wormald was also questioned at the inquiry over why he and the UK’s most powerful official, Mark Sedwill, were discussing how the virus was like chickenpox as late as mid-March 2020.

Wormald, who remains the permanent secretary in the department, believed Johnson “did not understand difference between minimising mortality and minimising overall spread”.

Lord Sedwill messaged Wormald weeks before the first lockdown, saying: “Indeed presumably like chickenpox we want people to get it and develop herd immunity before the next wave. We just want them not to get it all at once and preferably when it’s warn (sic) and dry etc.”

This message exchange came on the same day that Cummings had complained in a WhatsApp message that Sedwill had been “babbling about chickenpox”, adding “god fucking help us”.

Giving evidence to the inquiry this week, Cummings claimed that Sedwill had told Johnson: “PM, you should go on TV and should explain that this is like the old days with chickenpox and people are going to have chickenpox parties. And the sooner a lot of people get this and get it over with the better sort of thing.”

Stevens also told the inquiry that senior ministers “sometimes avoided” Cobra meetings chaired by Hancock in the early days of the pandemic.

In his witness statement, he said the meetings “usefully brought together a cross-section of departments, agencies and the devolved administrations”.

“However, these meetings were arguably not optimally effective. They were very large, and when Cobra meetings were chaired by the health and social care secretary other secretaries of state sometimes avoided attending and delegated to their junior ministers instead,” he added.

This phase of the Covid inquiry assessed government decision making, with more witnesses scheduled to appear next week.

These include Sedwill, former No 10 special adviser Dr Ben Warner and former home secretary Priti Patel.

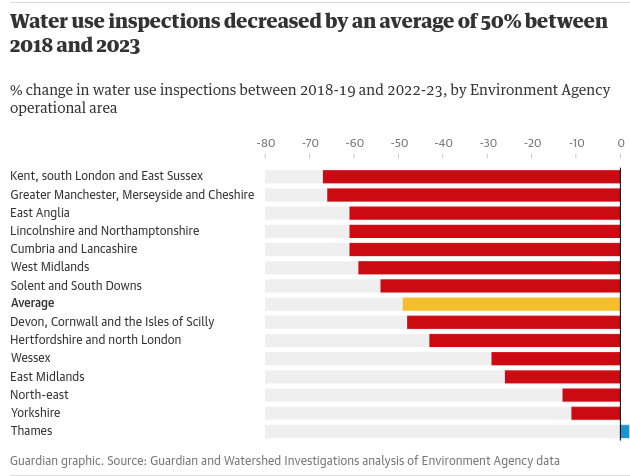

The Environment Agency has slashed its water-use inspections by almost a half over the past five years, it can be revealed.

[Including Devon & Cornwall]

Rachel Salvidge www.theguardian.com

Environment Agency (EA) officers visited people and businesses with licences to abstract, or take, water from rivers and aquifers 4,539 times in 2018-19, but this dropped to 2,303 inspections in 2022-23, according to data obtained by the Guardian and Watershed Investigations.

The fall in inspections comes despite England facing a possible water deficit of 4bn litres a day by 2050 unless action is taken, and predictions that the summer flows of some rivers could dwindle by 80% in that time.

“Obviously, this is highly beneficial to water companies and agriculture, and incredibly detrimental to water resources and therefore the environment,” an EA insider told the Guardian and Watershed on condition of anonymity. Last year, the Guardian reported that the EA did not have a strong grasp on the total volumes taken from rivers and groundwater.

The agency has also introduced desk-based inspections, which the insider described as meaningless. “They are a substitute for field inspections, and given an officer needs to check meters or records, or on-site behaviours, they are useless except for ticking a key performance indicator box.” The EA says it only uses desk inspections to assess compliance of low-risk abstraction and impounding licences.

“By reducing inspections you reduce the ability to detect illegal activity and gather evidence against,” the insider said. “Desk-based inspections are solely reliant on the word of the operator, so, for example, if an operator tells an Environment Agency officer he hasn’t abstracted any water, then the officer records that as fact. If it is an illegal operator, they are unlikely to hand themselves in. These methods provide a smokescreen of numbers that suggest correct regulation is being carried out should anyone try to audit it, when in reality the regulation is meaningless.”

Figures obtained by the Guardian and Watershed Investigations show that the biggest drop in inspections was in the Kent, south London and East Sussex area, where inspections fell 67% – from 450 to 148 between 2018-19 and 2022-23. This was followed by Greater Manchester, Merseyside and Cheshire, where the number of inspections dropped from 139 to 47. In East Anglia, 824 abstraction inspections fell to 318, and in the Lincolnshire and Northamptonshire area they dropped from 173 to just 67.

However, an EA spokesperson said the insider’s interpretation of the drop in numbers was misleading because “inspection figures alone are not the only way of assessing whether those who take water from the environment are complying with their licences – satellite data, irrigation patrols, river gauges, groundwater level and ecological monitoring systems are increasingly used. This allows us to target activity to where and when the risks are highest and the environment is most vulnerable.”

Despite the total funding for the agency’s water, land and biodiversity area business group having risen by £73m, from £221m in 2015-16 to £294m in 2021-22, staff costs for roles in land and water management, groundwater, contaminated land and environmental monitoring fell by £2.6m (9%) over the past three years.

“The Environment Agency leadership have received vast increases in money to tackle the issue, but this has been deliberately moved away from the frontline,” said the insider. “This means they must not view protecting water supplies as a priority and that the money could be better spent elsewhere.”

The EA spokesperson said the regulator was “recruiting and training more staff to carry out water resources compliance work and … also strengthening the way we regulate to drive better performance from the water industry, with additional specialist officers and new data tools to provide better intelligence”.

Public water supply and rivers are at risk from intensifying droughts driven by the climate crisis. The chair of the EA, Alan Lovell, said about 4bn extra litres of water would be needed every day by 2050 if significant action were not prioritised, and the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology has predicted that some rivers could lose up to 80% of their flows in summer by 2050.

Meanwhile, water sector leaks remain high, with the Environment Agency putting the volumes of water lost at 2.3bn litres a day last year.

A spokesperson for Water UK said water companies were “acutely aware of the environmental impact of abstraction and are proposing to stop half a billion litres’ worth of abstractions from rivers by 2030. Companies also have ambitious plans to cut leakage, which has come down every year since 2020, by a quarter by the end of the decade. To ensure the security of our water supply in the future, water companies are planning to build up to 10 new reservoirs as well as looking at alternative supplies of water including water recycling and desalination.”

Richard Benwell, the CEO of Wildlife and Countryside Link, said: “A long-term funding drought for the Environment Agency has left it under-resourced for the water challenges ahead. Recent funding rises don’t offset the years of underinvestment in the agency.

“This drop-off in post-Covid inspections is highly worrying and runs the risk of failures going under the radar. Desk-based and industry self-assessments simply aren’t up to the task, as we’ve seen with the sewage pollution crisis.”