It is now being widely reported that Steve Reed, Secretary of State for Housing, Communities and Local Government, would be making £63 millions available to local authorities undergoing reorganisation to fund the reinstated elections.

Category Archives: Misc

Breaking: Bad News for Turkeys in latest U-Turn

Prime Minister Keir Starmer has abandoned plans to postpone local elections for councils in May in yet another U-turn for the government. Source: Independent

Labour had initially announced plans to cancel elections in 30 areas this year, impacting 4.5 million people, in order to free up “capacity” to undertake an overhaul of council structures.

A Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) spokesperson said: “Following legal advice, the Government has withdrawn its original decision to postpone 30 local elections in May.

“Providing certainty to councils about their local elections is now the most crucial thing and all local elections will now go ahead in May 2026.”

The news was welcomed by Reform UK leader Nigel Farage, who said “we took this Labour government to court and won.”

County Council welcomes major step on SEND funding while highlighting wider pressures on local services

Government “clears the decks” ahead of reorganisation but is still scratching its head (if it has one) about a long term solution. – Owl

Chris Collman www.devonairradio.com

Devon County Council has welcomed the Government’s announcement that it will fund 90 per cent of local authorities’ historic Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND) deficits.

The decision represents a significant step forward for children, young people and families, and will help stabilise SEND finances, allowing more of Devon’s own resources to be directed into improving support and outcomes for children.

Councillor James Buczkowski, our Cabinet Member for Finance, said:

“This is a very welcome announcement and a major step forward.

“It gives the council greater financial stability in SEND and allows us to focus more of our resources on improving frontline support for children and young people.”

The announcement comes after years of rising demand and costs in SEND services, during which councils have been required to manage increasing pressures within a funding system that has relied heavily on local council tax.

While we welcome the Government’s commitment on SEND deficits, the wider financial pressures remain, particularly in adult social care, children’s services and the cost of delivering services across a large and largely rural county.

Councillor Buczkowski added:

“For too long, councils have faced rising demand while the balance of funding has shifted away from national government and onto local taxpayers.

“Today’s decision (Monday 9 February) helps to relieve some of that pressure in SEND, and that is good news for families across Devon.

“We now need to work through the detail of the announcement, but this puts us in a stronger position to set a 2026 budget that is focused on supporting children and young people and protecting vital services.”

We will now assess the detailed implications of the Government’s announcement as part of its budget-setting process.

The draft 2026–27 budget will be considered by Cabinet on Tuesday 17 February, with Full Council asked to formally approve the budget on Tuesday 24 February.

BBC reports: Julian Brazil, the leader of the county council, said it was a relief but added that councils needed more money to deal with ongoing costs in providing services.

The government, which is due to publish its plans shortly for a reform of SEND services, said the deficits had “threatened [the] council’s sustainability”.

Glory, glory, hallelujah!

“Battle Hymn of the Empire” – Marsh Family adaptation of “Battle Hymn of the Republic” about Trump

The “Battle Hymn of the Republic” is an iconic American song, drawing on lots of roots and precursors, but pulled into its most famous shape by abolitionist Julia Ward Howe. During the American Civil War it became a signature marching song for the Union Army, linked to patriotism and faith, and has since become part of the canon of American national music. We do not attempt or treat it lightly, but our version reflects on how the first week of 2026 has already seen Trump’s troops advancing his domestic and foreign policy agendas. Every marching step is another step away from the principles and traditions embedded in the song: we have seen the transgression of international law in Venezuela, the murder of unarmed Americans in Minneapolis (and its defence by the administration), the US’s withdrawal from multiple international organisations, and explicit threats issued to other sovereign powers and polities, including Greenland.

Have thine eyes seen the glory of the coming of the Lord? – Owl

Do potholes help police catch drunk drivers in Devon?

Letter to The Times 7 February:

Sir, In Devon we have our fair share of potholes. Rumour has it that this situation is helping our local police tackle drink-driving. If any vehicle is seen driving in a straight line, the driver is considered to be drunk.

David Lavender

Kingsbridge, Devon

Government opens seven week consultation on five proposals for Devon reorganisation.

The Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) has just launched a consultation on the five proposals submitted by various councils and combinations of councils on how to abolish district councils in Devon.

Responses can be made by completing an online survey, or in writing sent by email or by post. Closing date is 23:59 on 26 March.

However, Owl finds things aren’t quite as simple as they might seem.

Firstly, the proposals actually submitted last November differ somewhat from those discussed and reported by Owl during 2025. For example, South Hams, West Devon and Teignbridge have now broken from an earlier consensus amongst the districts; and County has made significant changes to the composition of its 3 unitary proposal.

Secondly, the online survey appears to have to be completed for each of the five proposals and there are ten questions. [Owl will check this].

Thirdly, respondents, even in writing, have to make clear where they are coming from and which proposal they are addressing.

Owl intends to take a few days digesting the related web pages and maybe stabbing a talon or two into the survey.

Meanwhile, the BBC has a good summary here

Worth reminding readers that the target population size for a unitary authority remains 500,000 and not even Plymouth comes near, let alone Torbay or Exeter.

With the councils in disarray, Owl’s view is that it is imperative that readers respond to this consultation and give their views. London based Ministers and the Mandarins of Whitehall have no real feel for the more remote parts of the country. They will see places like Devon as a quaint little place for a jolly holiday or even a second home. They need feedback from us who live and work here.

Plan for 63 homes lands on controversial ‘hedge destruction’ site

Owl’s attention was drawn to the apparent confusion over the applicant’s identity, see the last two paragraphs.

Developers are making a renewed bid for a 63-homes plan on land where a hedgerow was destroyed and efforts were made to protect mature trees from being cut down.

Bradley Gerrard, Local Democracy Reporter www.devonairradio.com

The prospect of homes on the site, based on land east of Sidmouth Road in Ottery St Mary, have previously proved controversial, but the location has become even more contentious after the unexpected removal of hedgerows and trees.

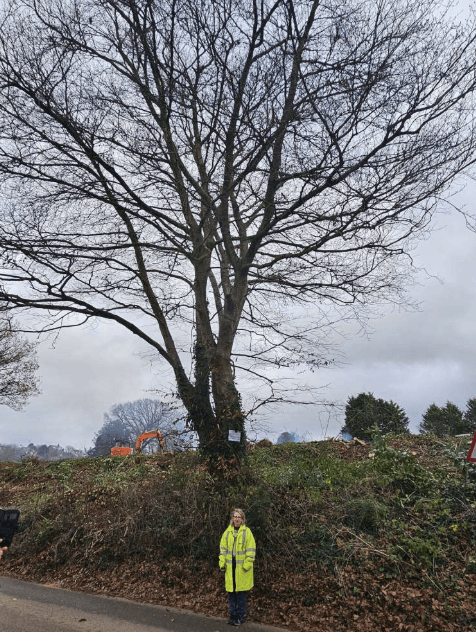

Back in December, Councillor Jess Bailey (Independent, Otter Valley) who represents the Ottery area on Devon County Council and East Devon District Council (EDDC), stood under one tree to prevent it being chopped down by contractors with chainsaws.

She also secured an emergency order to protect the remaining trees, and sought enforcement in relation to the hedgerow destruction.

A statement from the council, seen by the Local Democracy Reporting Service, states that it believes “hedgerow regulations have been breached in this case”.

“This is because the works that have been carried out have removed most of the previously unmanaged hedgerow along the western boundary,” it said.

“There are some remaining tree stumps present along the western boundary that may rejuvenate, however, large sections of the hedgerow have been damaged or removed and will not regenerate.”

It added the presence of gnawed hazel nut “provides confidence the area was used as a resting site for hazel dormouse” meaning the hedge would be “considered as important due to the presence of a Schedule 5 protected species”.

The email states the landowner had been given 14 days to explain their position, and that the council may, depending on the answer, consider a hedgerow replacement notice.

“But that could be subject to appeal and so we need to ensure we have all the facts before we decide on that,” the statement said.

Interestingly, the latest plans claim that it would be possible to “achieve a 9.66 per cent gain in habitat units and 12.73 per cent gain in hedgerow units, using the biodiversity metric” – suggesting the developer believes work can be carried out in conjunction with the prospective homes to help accommodate more flora and fauna.

This controversy about the scheme comes on top of the fact an application at this site has previously been rejected by EDDC.

The plan for up to 63 homes on the land was refused by East Devon’s planning committee in November 2023, and an appeal was subsequently dismissed by the government’s Planning Inspectorate in December 2024.

Part of East Devon’s reason for refusal related to the fact the site was an area of open fields, and the application included the “removal of a hedgebank to provide vehicular access and visibility splays [which] would have a harsh and harmful urbanising effect on the character and appearance of the area”.

“The resulting development would fail to respect the local distinctiveness or maintain the rural qualities evident in this landscape,” the decision stated.

The new proposal is an outline one, meaning that even if it is passed by the EDDC planning committee, a subsequent plan would be required to confirm details such as the layout of the development and design of the properties.

The new plans state the northern and eastern boundaries of the site are demarcated by hedgerow, while the western boundary is formed by Sidmouth Road. It adds that the site is currently being used sporadically and informally as agricultural grazing land.

The developer adds that across the road from the proposed site is a development of 45 homes.

Documents state the new plan proposes a mix of housing, ranging in size from two- to four-bedroom houses with gardens and associated parking.

“To reflect the character of the area, the proposed dwellings are two-storey and will be consistent in terms of mass and style with adjoining development,” the plans state.

“The scheme includes provision for 50 per cent affordable housing – equivalent to 31 units based on a scheme of 63 units.”

A spokesperson for the agent, XL Planning, said the firm did not wish to comment on the application.

The planning application form states the applicant as a Mr Davis of ALD Developments. Companies House data suggests that firm was dissolved in 2016, but has essentially been replaced by Proper Flap & Jack Investments. Both companies list an Adam Lloyd Davis as being linked to the company.

Proper Flap & Jack does not appear to have an official website.

Richard Foord MP dares to ask the $75,000 question

Richard Foord Liberal Democrat, Honiton and Sidmouth

The Epstein files suggest that Lord Mandelson was prepared to lobby in the United States in 2009 for a policy position in contradiction to that of Her Majesty’s Government, in which he was then serving as Business Secretary. Will this revelation encourage the Government to find out whether Lord Mandelson lobbied against his Government while serving last year as British ambassador to the United States? Can the Chief Secretary to the Prime Minister find out whether this lobbying against British Government policy is revealed in US policy towards the UK?

Darren Jones Minister of State (Chief Secretary to the Prime Minister), Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, Minister for Intergovernmental Relations

As I have informed the House today, the Cabinet Secretary is reviewing all documentation relating to Peter Mandelson’s time as a Minister in the last Labour Government to see what information is available today, and we will comply with any investigations that take place as a consequence. The hon. Member is right that any Minister acting against the collective decisions of Cabinet and against the Government is in breach of the rules. It is unacceptable behaviour, and if any Minister were to do that today, they would be quickly dismissed.

Source: US Department of Justice Release of Files Part of the debate – in the House of Commons at 4:57 pm on 2 February 2026.

But don’t hold your breath.

Pippa Crerar on X yesterday reported that

Gordon Brown says he has asked Cabinet Secretary to investigate disclosure of “confidential and market sensitive information” allegedly from Peter Mandelson to Jeffrey Epstein.

Former PM says he first asked CS (Cabinet Secretary) to do this in September but biz department (Department for Business & Trade) found no records.

He has “now written to ask for a wider and more intensive enquiry to take place into the wholly unacceptable disclosure of government papers and information during the period when the country was battling the global financial crisis.”

National press reports Devon LibDems railing against Labour’s “Stalinist” local government reforms

Read what Devon Leader Cllr Julian Brazil and Whimple and Rockbeare District Cllr Todd Olive have to say about Labour’s plans for moving to unitary authorities:

“It’s not devolution – it’s control freakery,”

“Stalin would be thrilled by the way we run our country; it’s so over-centralised. This in itself is a danger to democracy.”

Julian Brazil estimates that by the time this concludes it will have taken between 5 to 10 years and two-thirds of councillors will have lost their positions, leading to a professionalisation of local government, further diluting democracy.

On Exeter’s “go it alone” power grab Todd Olive said::

“They’ve cherry-picked major areas of growth around the airport and two new towns that will create [wealth for] Exeter unitary authority, but it will be a financial disaster for the rural and coastal authorities they’ll leave behind –they will be bankrupt within a year.”

Context

Labour wants to abolish District Councils, creating large consolidated unitary authorities with populations of around half a million or more. This will inevitably mean that residents will be represented by fewer councillors in larger electoral areas, all in the name of “devolution”.

District Councils in Devon typically spend around 7% of Council Tax. The essential localised services they provide such as: managing household waste, public spaces, council housing, addressing homelessness; managing public health issues; collecting council tax and administering relief; supporting local business, dealing with planning etc. will still have to continue at the same scale – so just how much of this 7% do the government think can be saved to offset the £50m estimate of making these changes in Devon? – Owl

The councillors up in arms against Labour’s £50m ‘Stalinist’ reforms

The Government calls it devolution. Opponents see a democratic deficit as power drifts further from local communities

Anna Tyzack www.telegraph.co.uk

Amid a roster of responsibilities that includes improving outcomes for vulnerable children and tackling the crumbling roads in one of England’s largest counties, Julian Brazil, the Liberal Democrat leader of Devon County Council, now finds himself forced to divert great swaths of his day to a matter so asinine that he’s not ruling out revolt.

Labour’s sweeping plans to tear up local government – reconfiguring some 63 local councils so that they fall into vast, unitary authorities – represent a demand he argues councils like his can ill afford.

“There’s a mood within councils – we’re fed up,” he says. “We’re trying to deliver children’s services and adult social care and the last thing we need is to spend hours and hours discussing something that could well be no better in the end. If enough councils go on strike, maybe the Government will listen?”

The Telegraph has been campaigning against the postponement of elections – a move which is meant to facilitate exactly these reconfigurations. Councillors across the country, meanwhile, are up in arms about the reforms themselves.

The English Devolution White Paper, originally launched by Angela Rayner, set out plans for a major reorganisation of local government, described by Labour as the “greatest transfer of power from Whitehall to the town hall in a generation”.

The postponement of local elections is designed to provide councils with the breathing space to implement these plans and has led to concerns about a democratic deficit in vast swaths of the country. And critics warn that the reforms themselves will result in a permanent blow to democracy. Larger unitary authorities will make councils more remote from the communities they serve, weakening the direct connection between residents and their elected representatives.

In June last year, the think tank Localis warned that shire areas in particular faced losing some 90 per cent of their councillors. “Local government will get less and less local,” said Steve Leach, emeritus professor of local government, De Montfort University. “And areas that have been used to their own elected council will be subsumed into meaningless conglomerates that will make no sense as units of local government and even less sense to local people.”

Added to this already worrying prospect, councillors are fearful over the cost of reorganisation, which is likely to spiral into the tens of millions (£50m in the case of Devon), as well as the fact that for many it feels like the mergers are being imposed from above. Ministers insist the process is locally led, yet the current legislative framework permits reorganisation to proceed without unanimous consent from all councils in an area.

Surrey is a good example. Surrey County Council, along with 11 district/borough councils are being replaced by two new unitary authorities, East Surrey and West Surrey. The Government set aside a proposal from nine of the eleven district councils for a three-way split, instead mandating a two-unitary model.

For Brazil, the pace at which councils are expected to reform feels particularly punitive. Eligible councils had to submit their proposed new footprints to the Government by November last year; the Government intends to have made a decision on the delineation of each region by summer recess this year (July), leaving areas a 20-month window to reorganise (the entire system is to be overhauled by the end of the current Parliament in 2029).

“There’s absolutely no way we’re going to get the timetable through,” Brazil complains. “It’s taking up an inordinate amount of time and money and they keep moving the goalposts. They’ve bitten off more than they can chew and they need to stop.”

“It’s not devolution – it’s control freakery,” Brazil says. “Stalin would be thrilled by the way we run our country; it’s so over-centralised. This in itself is a danger to democracy – a dangerous precedent was set.” Brazil was at the County Council Network’s recent conference and said he did not meet a single councillor in support of local government reorganisation.

For Todd Olive, a Lib Dem councillor in Devon, the drive toward huge, consolidated councils feels like a direct attack on political diversity. Opponents of reorganisation warn that creating large unitary authorities with populations of around half a million or more inevitably reduces the total number of council seats and expands electoral areas, trends that historically favour larger national parties and make it harder for smaller parties, independents and truly local voices to win representation.

Analysis by the Local Government Association’s Independent Group on the political and governance effects of reorganisation has warned that such changes are likely to diminish the influence of independent and smaller-party councillors, as fewer seats are contested across broader areas and party machines gain an advantage. “We’re suspicious this is about getting rid of the smaller-scale political campaigning we’re effective at as a party,” says Olive, “and creating super councils dominated by legacy authorities.”

Phoebe Sullivan – an opposition Conservative councillor in the Lib Dem-led Waverley Borough in the Conservative-led Surrey County Council – raises a related concern about representation, warning that as councils and electoral divisions grow larger, smaller communities risk being overlooked.

Even though Sullivan is broadly supportive of reorganisation in principle, she worries that villages are losing their distinct political voice. In her own patch, the villages of Witley and Milford in Surrey – previously a ward in their own right – have been subsumed into a much larger division now labelled “Godalming and Villages”, a change she fears could leave village priorities overshadowed by those of the town.

“Councillors are likely to be Godalming-focussed,” she says. “It’s all done by density; the more dense the population the more focus they get, but rural villages need a voice as well. Villages will be let down by local government reorganisation.”

Councillors elsewhere have taken issue with a group of Cathedral cities – including Exeter, Ipswich and Oxford – who they argue are attempting to expand their borders and influence. “It’s gerrymandering. A land grab. Nothing about delivering the best services to residents,” Brazil says.

Olive, who is a councillor for the villages of Whimple and Rockbeare on the fringes of Exeter, describes the city’s plans to swallow up villages as “a bit like parking tanks on our lawns”.

These councils could seize control of affluent outlying areas; Whimple and Rockbeare are home to Exeter airport and various business parks, which would all offer a boost to the city council’s revenue (via business rates) and to its status.

“We don’t want to be part of Exeter,” he says. “They’ve cherry-picked major areas of growth around the airport and two new towns that will create [wealth for] Exeter unitary authority, but it will be a financial disaster for the rural and coastal authorities they’ll leave behind – they will be bankrupt within a year. Those parts of Devon don’t have the growth points and economic centres that enable councils to do OK.”

Brazil and Olive fear that in Devon it won’t be senior management losing their jobs during the merger – but local councillors. Brazil estimates that by the time the restructuring is complete, two-thirds of councillors will have lost their positions, leading to a professionalisation of local government, further diluting democracy.

Olive, who is 27 and still living with his parents, says that he will not stand under the new system despite being passionate about local politics and the needs of communities – he can’t afford to. Already his council work takes up at least half the week; under the new system, where councillors will be overseeing much larger areas, it would be a full-time job. “It’s becoming inaccessible to people who aren’t independently wealthy. If only one type of person is standing, you lose all of the diversity,” he says.

Sullivan agrees that lack of diversity is an inherent problem in local government, which the threat of reorganisation is doing nothing to tackle. She’s 29 and works in the private sector; if her boss wasn’t flexible about her attending council meetings during the week, she wouldn’t be able to stand as a councillor. “Statistically, the system doesn’t entice or accommodate working professionals, mothers or young people,” she says.

Although she argues that it’s not all doom and gloom – the thinking behind the new system is that middlemen will be cut out, saving time and resources – “at the moment it’s just a lot of tangled-up admin”.

Still, if Labour genuinely intends to place power in the hands of “local people with skin in the game”, as Angela Rayner once put it, Brazil argues that the Government should allow those communities to manage their own local government reorganisation without central interference.

The “cliff edge approach” in particular is fraying Brazil’s nerves and he’s looking into ways to protest, without hurting residents. “We’ll deliver unitaries to you in five or 10 years but don’t give us a ridiculous timetable,” he fumes.

“They talk about devolution and then tell us how to do it. They can’t even run their own Government. It’s not the town halls that need reorganising – it’s Westminster.”

Alison Hernandez – starts her long departure with a bang!

[Police Commissioners are to be abolished in 2028]

Proposal to raise council tax for police funding – Increase of 5.2% on the cards

(Now approved – Owl)

Residents across Devon and Cornwall may have to pay more towards policing in their council tax.

Radio Exe News www.radioexe.co.uk

The Police and Crime Commissioner for Devon, Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly, Alison Hernandez, will propose an increase of 5.2% a year.

This increase would be £15 a year for an average Band D property.

Ms Hernandez said she feared officer numbers would be at risk if councillors on the Panel did not approve the increase, after a government grant settlement which has left the force with a budget shortfall or around £3 million for 2026-27.

43% of the funding for Devon and Cornwall police comes from council taxpayers, a far higher proportion than many other parts of the country, with the rest of the budget coming from central government.

The government caps the amount that police commissioners are allowed to increase council tax at £15 for a Band D property, but even with the maximum increase allowed, the budget for Devon and Cornwall Police will rise by 4.2% in 2026-7 compared to the national average of 4.5%.

Commissioner Hernandez said: “The new government settlement appears to effectively penalise the force for this success in meeting national recruitment targets by removing base funding for those officers.

“Across England and Wales the average grant increase for policing is 4.5%, however in Devon and Cornwall that figure is 4.2%. Only four policing areas in England have had a lower provisional settlement than Devon and Cornwall. This leaves me with an anticipated shortfall of around £3million and no choice but to ask taxpayers to pay more.”

The Commissioner says the Chief Constable has assured her the funding gap is unlikely to affect the total number of officers which remains at the record high of 3,610, because of £6 million of locally identified efficiencies already planned in next year’s budget.

One of other the reasons the force is not likely to have to reduce the number of officers is that the two counties have a very high proportion of second homes (charged 200% council tax). Last year council tax contributions from second homeowners raised £6million, with a similar amount expected in 2026-27.

“Our communities deserve visible, effective policing. We have worked hard, alongside local taxpayers, to increase officer numbers to their highest level ever. It is deeply concerning that we now appear to be punished for doing exactly what government asked of us.”

“Many families are already under immense financial pressure, and I do not believe it is fair for the only option to be to ask people to pay even more. I have always committed to our local taxpayers that if they pay more they get more. For the first time, I’m going to have to ask people to pay more to get the same or less.”

Can’t afford elections but Exeter joins the race to become “City of Culture 2029”

No effort or money to run elections, he claims. Now we discover not only is Cllr “Turkey” Bialyk struggling to pursue his ambition to take over neighbouring districts he is also bidding for Exeter to become “City of Culture in 2029”.

It’s all a matter of priorities.

See below for what’s involved in this latest “distraction”. – Owl

Exeter is putting in a bid to become the UK City of Culture in 2029.

Chloe Parkman www.bbc.co.uk

The city council said it would be submitting an expression of interest, joining other locations including Plymouth, Bristol and Portsmouth in the race to win the title.

The winning city will be awarded £10m in funding to create a year-long celebration of arts and culture.

Council leader Phil Bialyk said the bid would help raise the city’s profile and show Devon is not just about “scones and cream”. The deadline for entries is 8 February.

The council said its bid followed five months of extensive engagement and consultation with artists, creatives, cultural organisations and residents to shape a five-year Cultural Strategy for Exeter.

Bialyk said it was a fantastic opportunity for the city and added “it’s a chance to put Exeter once again on the national and international map”.

He said the city already had “so much going on” in terms of arts, culture and leisure.

“Following two rugby world cups in the city – the men’s in 2015 and the women’s last year – we have more than demonstrated Exeter’s ability to rise to the occasion and host big international events that put culture at the heart of our offer,” he added.

“We want to grow, we want good jobs, we want good people, we want homes and we believe the City of Culture will be exactly the right thing for Exeter.”

Analysis from Miles Davis, BBC Devon political reporter

It’s the timing of this announcement that is most interesting – coming only two weeks after Exeter City Council’s leader cancelled elections due to be held in May.

When he cancelled those elections, the Labour leader Phil Bialyk said it was to save money and that council staff were overloaded with work trying to prepare for the reorganisation of local government which will see Exeter City Council and many other councils abolished by April 2028.

But now it seems there are staff and resources available to prepare a bid to become the UK City of Culture.

The potential rewards are clear but with cities and towns from Plymouth to Blackpool all entering the contest – competition will be fierce.

What a bid involves – Owl

Here are some extracts from the Department for Culture,Media & Sport’ Expression of Interest: Guidance for bidders

Benefits of bidding

We know that bidding for the title – not just winning – can have a hugely positive impact on a place. The process of preparing a bid can help to bring partners together and develop strategic cultural leadership, showcasing and opening up access to your local culture, art and heritage, and articulating your ambitions for the future. We know from previous competitions that these ideas and partnerships can, and often will, carry on irrespective of whether a bid is ultimately successful and many previous bidders have gone on to realise elements of their bids despite being unsuccessful in this competition.

The last competition received a record number of bids and this time around we want as many places as possible from across the UK to have the opportunity to draw on the benefits of bidding. We have designed the competition with this in mind: with a light touch initial EOI stage and funding to support bidders in the later stages of the competition, as well as for runners up. We would encourage bidders to think about how you would use DCMS funding and work with partners to take forward elements of your bid, even if you are not selected as UK City of Culture 2029.By 9 February bidders have to submit an initial “Expression of Interest” (EOI).

To be successful, EOIs must demonstrate how they meet the criteria and show potential to make a significant contribution to the aims of the UK City of Culture programme. There are six aims and 20 criteria:

UK City of Culture 2029 competition aims and criteria

| Aims | Criteria |

| 1. Share and celebrate a uniquely local story and vision which uses culture and creativity to transform a place | 1. Vision: Articulate a strong and unique vision for your place and programme, informed by communities and underpinned by a compelling local story which uses the catalytic effect of culture and heritage to bring people together, building a sense of place and inspiring local pride. 2. Leadership: Demonstrate a strong, collaborative leadership approach with clear commitment and involvement from local authorities, community organisations, and the cultural sector, ensuring a credible long-term cultural legacy. 3. Local need: Set out a programme and legacy that is shaped by communities and uses culture to respond to and address specific local priorities and targets those that are most in need. 4. Transformation: Present a strategic understanding of what ‘transformation’ means for your place and how it can deliver a measurable and sustaining step change for people and place, including the articulation of clear social, wellbeing and economic impacts. |

| 2. Create transformative opportunities and richer lives for people and communities | 5. Opportunity: Create increased opportunities for everyone, especially young people, to access and participate in culture. 6. Empower: Demonstrate commitment to actively including local communities, grassroots artists and creatives, and regional and local leaders in decision-making. Also demonstrate commitment to supporting them to directly shape the bid, programme and legacy, devolving decision-making power to communities where possible. 7. Cohesion: Promote and increase community cohesion, engaging and inspiring local communities to volunteer and bring people together by creating spaces and opportunities for social mixing. 8. Pride: Build a sense of belonging and inspire local and national pride. |

| 3. Create a sustainable economic impact by delivering good jobs and boosting growth in your place or wider region | 9. Context: Show a clear understanding of how your proposal fits with and strengthens wider regional or national growth plans. 10. Growth: Increase investment in culture and creativity, leading to higher productivity and output, to enhance the profile of the area as a cultural destination, leading to boosted tourism and new investment to drive inclusive growth. 11. Jobs: Increase local employment opportunities in the cultural and creative industries – before, during and beyond your programme year. 12. Skills: Increase inclusive opportunities for the development of specialist and life skills and for routes into creative and cultural careers, including for but not limited to young people. |

| 4. Champion quality and innovation | 13. Quality: Deliver a high quality cultural programme that builds and expands on local strengths and assets, and draws on the best of the UK’s art, heritage and creative industries to contribute to the UK’s reputation as a world-leader in the cultural and creative industries. 14. Innovation: Demonstrate cultural and artistic excellence, creativity and innovation, including through using technology to open up access to culture. 15. Environmental responsibility: Embed environmentally sustainable practices into the programme and its legacy, demonstrating contribution to the UK’s Net Zero and nature protection objectives, and promote and inspire environmental responsibility. |

| 5. Reach out locally and across the UK to work with a range of diverse partners | 16. Shared story: Strengthen and celebrate connections with places across the four nations of the UK (and also internationally, if important to your place and its story), drawing on culture and heritage to collaboratively tell our shared story through an outward-looking and highly inclusive programme. 17. Partnerships: Collaborate with a broad range of local, regional and national partners (and also international, if important to your place and its story), actively pursuing new opportunities and making meaningful and lasting connections that contribute to your place’s long term vision. |

| 6. Maximise the legacy of the UK City of Culture programme | 18. Evaluate: Present a robust and achievable evaluation plan and methodology to monitor and evaluate the impact and expected step change of the programme, drawing on previous winning places. 19. Embed: Demonstrate a clear understanding of how the programme aligns with and/or embeds into existing local cultural strategies beyond 2029, or how the programme can be used as a catalyst to develop a cultural strategy which aligns with existing local strategies. 20. Sustain: Present an ambitious and robust plan that demonstrates how the strategy underpinning the programme will deliver a strong ecosystem of cultural and creative organisations rooted in and actively shaped by the community, and strengthen local leadership, partnerships and capability. |

‘My part of Devon submerged and needs better flood defences’, Richard Foord MP demands

A Devon MP has pushed for greater financial support for flooding after telling Parliament that his part of the county was “submerged” amid this week’s storms.

Bradley Gerrard, Local Democracy Reporter www.devonairradio.com/

Richard Foord, the Liberal Democrat member for Honiton and Sidmouth, addressed the weekly Parliamentary landmark event, Prime Ministers Questions, with his push for better support, as parts of his constituency found themselves fighting a losing battle against flood waters.

Looking towards Otterton Mill left (Image courtesy: Melanie Martin).

“The Met Office reports that climate change is driving wetter winters, yet the US withdrew from the Paris Climate Agreement yesterday, on the same day that much of the westcountry disappeared under flood water,” he said.

“My part of Devon is submerged and needs better flood defences. Would the deputy prime minister like to invite his US counterpart for a fishing trip in the South West.”

David Lammy, the deputy prime minister who was standing in for the prime minister Keir Starmer who is in China, quipped that he would “get a licence if I do”.

However, he added that his “sympathies are with [Mr Foord’s] constituents who have been affected”.

“We are investing a record £10.5 billion in flood defences to protect 890,000 homes,” Mr Lammy said.

“We inherited the current flood defences from the party opposite, which were shameful, but we have committed to net zero and the Paris Climate Agreement, which is good for lowering bills, and investment and jobs in the UK.”

Mr Foord’s question came just after comments to the Local Democracy Reporting Service about the damage in his constituency from flooding.

“Storm Chandra has left a brutal trail of destruction across Mid and East Devon, with dozens of businesses and schools forced to close,” he said.

“I’ve been shocked at the pictures of communities under water, in ways that we have not seen for decades.

“I commend community-spirited residents and local farmers who have come to the rescue of people stuck in floodwater.”

He added that Ottery St Mary, Honiton, Axminster, Cullompton and Colyton were among towns affected, along with surrounding villages.

“I am particularly dismayed at the images of Tipton St John Primary School, whose grounds resemble a lake once again,” he said.

“The community here desperately needs plans progressed for a new school on higher ground in the village. I will work with local councillors to do what I can to bring this about.”

Mr Foord added the risk to life red ‘severe flood warning’ to the River Otter (one of only two such warnings in the UK on Tuesday 27 January), has now been lifted but a flood alert remains in place.

Honiton “goings on” spring from the uncertainty and power vacuum created by the government

At the moment no-one in Devon knows where we are going under the proposed local government reorganisation, except that district councils, the ones we are probably most aware of, are being abolished in the name of efficiency.

Ironically District Councils are the ones who collect Council Tax but East Devon only spends about 7% of it, not much more than is spent by towns and parishes.

Perhaps it’s not surprising that Honiton is hedging its bets by filling its coffers in what looks like an attempt to “take back control” and fill the vacuum. See how Honiton wants a 49.9% hike in precept].

As the press report referenced in the previous paragraph suggests, Honiton may not be the only town council doing this.

Honiton’s “vision” can be found on this link and more in depth press reviews following Owl’s post on Jo Fotheringham’s resignation can be found here.

Owl thought it might be helpful to review the back story: the evolution of local government; and wonders how far Honiton can rewind the clock.

Formation of East Devon District Council in 1974

East Devon District Council (EDDC) was formed in 1974.

It covers the whole area of eight former districts and part of a ninth, which were all abolished at the same time (many will be familiar names, others like St Thomas Rural which had its offices in Southernhay East, may not be):

- Axminster Rural District

- Budleigh Salterton Urban District

- Exmouth Urban District

- Honiton Municipal Borough

- Honiton Rural District

- Ottery St Mary Urban District

- St Thomas Rural District (parts north-east of Exeter, rest went to Teignbridge)

- Seaton Urban District

- Sidmouth Urban District

The purpose, surprise, surprise, was to make efficiency and cost savings.

Before 1 April 1974, there were 1,211 local authorities in England. In many cases towns were governed by separate authorities from their rural surroundings. A 1971 White Paper proposed rationalisation for the following reasons:

“The areas of many existing authorities are out-dated and no longer reflect the pattern of life and work in modern society. The division between counties and county boroughs has prolonged an artificial separation of big towns from their surrounding hinterlands for functions whose planning and administration need to embrace both town and country.”

The reform created a more standardised pattern of 45 county councils and 332 district councils, though in the six metropolitan counties the division of functions between the two tiers was different from elsewhere.

This produced a reduction of about 75% in the number of councils.

The White Paper also stated that “local authority areas should be related to areas within which people have a common interest – through living in a recognisable community, through the links of employment, shopping or social activities, or through history and tradition”.

This Act was hugely controversial at the time. It established some new counties and merged others.

It also ended the freedoms of ‘county boroughs’ – large towns and cities that had been allowed, in effect, to opt out of county council ‘control’ and run county services in their areas.

Nevertheless, these reforms were considerably less radical than those proposed by the 1968 Royal Commission on Local Government (the Redcliffe-Maud report)

Redcliffe-Maude redux?

Has Sir Humphrey run out of new ideas or is there really nothing new to add to the Redcliffe-Maude report? It looks suspiciously like the starting point for what the government is now seeking.

The 1968 Royal Commission proposed 58 unitary authorities to cover the whole of England outside of Greater London, plus three two-tier areas based on Birmingham, Manchester and Liverpool.

[Note that 58 unitary authorities are just where we are headed now!]

The current 2025 reforms are aiming at creating between 2 or 3 unitary councils in place of each county council and its associated districts, effectively producing a similar reduction to that achieved in 1974.

It is also worth noting in the detail that Radcliffe-Maud proposed that Cornwall should become a single Unitary Authority and Devon be split into two: Plymouth and Devon (with Exeter included in Devon).

Evolution of local governance from ancient boroughs, parishes and feudal systems

Local governance as we recognise it today started with the industrial revolution and consequential rapid increase in population and population densities.

Boards of improvement commissioners were ad hoc urban local government boards created during the 18th and 19th centuries to cope with things like street paving, lighting, cleaning and policing.

Local Boards of health were formed in response to cholera outbreaks in the late 19th century concerning themselves with sewage and water supply and general sanitary arrangements. These became particularly influential in the emerging Devon seaside resorts.

Local authority elementary education boards were established in 1870 to take over from church and charity education foundations; their remit was extended to secondary education in 1902.

What happened to the Localism Act 2011?

This Act aimed to shift power, responsibility, and resources from Whitehall to local councils, neighbourhood groups, and individuals, promoting self-sufficiency and local decision-making.

Not at all obvious to Owl that this is the direction we are heading towards.

Latest “goings on” in Honiton Town Council – Councillor resigns

It is a year or two since Owl reported on vocal disagreements in Honiton TC, though it does seem to have “Form” for walkouts and even mass resignations. [Search: Honton goings on]

Cllr. Joanne Fotheringham has just issued this press release:

HONITON TOWN COUNCILLOR RESIGNS IN PROTEST AT 50% INCREASE IN PRECEPT

Honiton Town Councillor Joanne Fotheringham has resigned from Honiton Town Council in protest at what she describes as “its speculative and poorly considered approach to public expenditure”.

Cllr Fotheringham said her decision follows growing concern over the Council’s financial direction, particularly its proposal to increase the council tax precept by 49.90%

This takes the precept from £667,545 to £1,000,645 which represents £243.43 per annum per Band D equivalent property, an increase of £81.03.

“I can no longer support the direction in which the Council is headed,” she said. “A 50% rise in the council tax precept is indefensible and reflects a hasty, back‑of‑an‑envelope response to uncertainty over Local Government Reorganisation, rather than a responsible, long‑term plan.”

She criticised the Council’s decision to allocate £120,000 for legal and other fees for Local Government Reorganisation, despite a reduction in the number of potential asset transfers, describing the fund as “increasingly resembling a slush fund for the Transitional Committee.”

Cllr Fotheringham also cited wider concerns about poor planning, pressure on council staff, and the misuse of public resources for exclusive events such as the Mayor’s Charity Ball.

She expressed particular frustration at the Council’s refusal to hold an open tender process for the Beehive lease, despite legal advice supporting it — a move she said “preserved the status quo and excluded alternative bids that might have better served the community.”

“Honiton deserves a council that serves its people honestly, efficiently, and with a sense of purpose grounded in financial and practical reality.” Cllr Fotheringham said. “Sadly, I no longer believe this Council meets that standard.”

Cllr Fotheringham concluded by thanking Council staff, praising their professionalism, dedication and good humour under difficult circumstances.”

Jumping Beans – A correspondent writes on switching allegiances and elections

Dear Owl,

I’ve read with interest your articles inEast Devon Watch regarding Exeter City Council elections being cancelled. I firmly believe that these elections must go ahead.

In my opinion, if any politician switches allegiances, a by-election should also automatically be triggered.

The MP for Exmouth and Exeter East and different councillors in his constituency have also been critical of Exeter Labour wanting to cancel the planned city council elections. I’m rather cynical because they’ve been less vocal about the need to have by-elections in cases where councillors have “crossed the aisle” after their election.

In September 2025, we read that the elected Reform UK Limited Devon County Councillor for Pinhoe and Mincinglake was expelled from his political party.

On Devon County Council website, he’s now listed as Independent with no political grouping.

But he appears to do the social media for Advance UK Limited – Exeter Branch and is critical of Exeter City Councillors.

Perhaps he should call a by-election as he was NOT elected to be an Independent county councillor with political allegiances to Advance UK?

In September 2025, we read that the elected Reform UK Limited Devon County Councillor for Wonford and St Loyes resigned from her political party.

On Devon County Council website, she’s also listed as Independent with no political grouping.

She hasn’t been vocal on social media about Exeter City Council elections being cancelled, but apparently she has had talks with Advance UK. Constituents might be grateful if she could call a by-election as she’s no longer a member of Reform UK Limited.

In December 2025, we read that the Conservative Exeter City Councillor for St Loyes ward defected to Reform UK Limited.

This councillor stood as a candidate for UKIP in 2015 and 2019 in this ward in Exeter City Council elections, but was unsuccessful in being elected. In 2023, she stood as a Conservative candidate and the former Conservative MP for East Devon posted pictures of them leafletting together. She was elected as the Conservative councillor for St Loyes in May 2023.

Since her defection, on social media her Conservative MP for Exmouth and Exeter East hasn’t called for a by-election in this ward. However, he has been vocal about the Exeter City Council elections being cancelled.

On social media, the Branch Chair of Exmouth and Exeter East Reform UK Limited, who is also a Devon County Councillor for Exmouth acknowledged the Exeter City Councillor for St Loyes defection but didn’t call for a by-election to be called for that ward. However, she has been critical of Labour Exeter City Councillors voting to cancel the local elections in May.

In September 2025, Danny Kruger, MP for East Wiltshire defected from Conservatives to Reform UK Limited. Last week, Robert Jenrick, MP for Newark defected from Conservatives to Reform UK Limited. On Sunday, Andrew Rosindell, MP for Romford defected from Conservatives to Reform UK. If the voters would have wanted a Reform UK Limited MP, they’d have voted for one.

Here are the formal results for each of these three constituencies:

Newark General Election – July 2024:

East Wiltshire General Election – July 2024:

Romford General Election – July 2024:

By not calling a by-election, these MPs have little regard to their constituents.

The Conservative MP for Exmouth and Exeter East hasn’t mentioned these defections on his social media. However, the Conservative MP for Meriden and Solihull East has posted the petition for requesting by-elections to be called automatically when an MP defects.

Please sign this petition if you believe that by-elections should be automatically triggered when MPs switch their political parties/allegiances.

Yours sincerely,

A cynical correspondent.

Devon Leader Cllr Julian Brazil on three letters from ministers

Perhaps the most significant concerns Local Government Reorganisation (LGR).

Cllr Brazil points out that LGR was was never part of Labour’s manifesto. Devolution was, but that’s now been kicked into the long grass.

Time for another U-turn! – Owl

Cllr Julian Brazil www.midweekherald.co.uk

I had three letters from ministers at the end of the year, writes Cllr Julian Brazil.

The first was from the Minister for Children and Families.

It’s good that he’s recognised the improvements we have been making, but like him, we understand this is just the beginning.

There is a long way to go, and we must remain laser-focused.

The threat of a trust model intervention still hangs over us.

It may be a legacy of over a decade of underperformance and failure, but the responsibility now lies with the new administration.

Invitation

I’ve been invited to a meeting with the minister.

I’m looking forward to it.

He wants to hear at first hand our plans.

We’ve been working on the strategy over the past few months.

It covers a whole raft of policies but at its core are prevention, early intervention and inclusion.

To get this right, we know we must work in partnership and that includes government.

I’m hoping it will be a two-way conversation.

More clarity around the whole Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND) agenda.

Stability around funding and, of course, delivering these services in a rural area.

Cancelling Elections

The second letter was from the Minister for Local Government and Homelessness.

Slipped out just before the Christmas break, it was about cancelling local elections this coming May.

Dressed up as a scheme to help overworked councils embroiled in local government reorganisation (LGR) and save council taxpayers money: you couldn’t make it up.

They must think we’re stupid.

Everyone can see it’s a rather shabby attempt to pervert the course of democracy.

It sets an incredibly dangerous precedent; if you’re going to lose an election, cancel it.

To be fair, Plymouth City Council swiftly announced they would be going ahead with their elections.

It was the honourable thing to do.

Exeter voted to cancel, despite howls of protest outside the Guildhall by the residents the council purports to serve.

Here we are with a government trying to cancel elections because, they claim, it’s all becoming too complicated with LGR.

Of course, LGR was never part of their manifesto.

Devolution was, but that’s now been kicked into the long grass.

Why can’t they just admit they’ve got it wrong?

Many of us can see what they’re trying to achieve, and we agree with a lot of it, but the way they’re going about it smacks of total incompetence.

When you’re in a hole, as the saying goes, stop digging.

Instead, the government has got the JCB out.

Control Freakery

The third letter was from the Secretary of State for Housing, Communities and Local Government.

I don’t know if he actually wrote it, but it’s one of the most disingenuous letters I’ve ever read.

To be fair, that’s not what really riled me; we’re getting used to this.

It was the thinly disguised and unashamed threat to micromanage a council in Cambridge.

It’s exactly what one of his predecessors, Michael Gove, tried to do.

Even he backed down when faced with academic research.

Struggling with recruitment issues, particularly around planning and legal officers, the council introduced the innovative strategy of a four-day work week.

In many ways, mimicking the private sector.

Whatever one’s views about the four-day initiative, that’s not really the point.

The thing is, you have a local council, elected by local people, delivering services in the best way it thinks it can.

If they fail, they can be voted out by the same local people.

It’s called democracy.

How outrageous that a SoS starts trying to throw their weight around.

Maybe he should spend more time helping his own government; goodness knows they need it.

Monster 700-home Exmouth plan threatened with objection

Despite the rain the BBC reported last night that the protest did take place.

Independent councillor, Melanie Martin, said: “This is a fantastic turnout considering the weather is so bad.

“It just goes to show how strongly people feel about this development of 700 houses.”

Exmo 20 – 3,500 responses have already raised concerns

Bradley Gerrard www.exmouthjournal.co.uk

Campaigners against plans for a monster 700-home development in Exmouth are trying to amplify opposition as the deadline for objections nears.

A Facebook group has been set up to try and publicise the plight, which is essentially vociferous opposition to a possible plan for up to 700 homes on the outskirts of the East Devon town.

The group, whose name is ‘Stop Exmo.20, Exmouth’ Supersize Development’ has alerted people to the deadline for responses, and even provided answers that residents can use to cut and paste into their objection.

East Devon residents are being asked for their views on the district’s local plan, which identifies areas where it is acceptable for homes to be built and commercial land to be created between now and 2042.

Residents have until midday on Monday 26 January to provide any comments on the plan, which can be submitted on a dedicated section of the council’s website known as Commonplace.

The site known as Exmo_20, which has courted the vast majority of opposition, would allow for the development of around 700 homes near St John in the Wilderness Church.

Even if the local plan is approved, developers would still need to submit planning applications for specific schemes, and these would need to comply with planning policy and secure the planning committee’s blessing to be approved.

Earlier this year, an initial public consultation on the local plan saw 3,500 responses from residents who raised a range of concerns.

But more than 1,100 of those were against the St John’s scheme.

Major fears related to potential harm to the nearby pebblebed heaths, which has four different designations aimed at protecting it, including being a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI).

Besides concerns from residents about the heaths, environmental organisations including Devon Wildlife Trust, the RSPB and Natural England also voiced their fears.

Some worried that the Grade II* listed St John in the Wilderness Church could be impacted by such a large development of homes, while others feared heightened flood risk due to the clay soils and upstream location relative to Withycombe Brook.

Members of the strategic planning committee, who are responsible for crafting the local plan, heard from members of the public at their July meeting, with the majority of those speakers outlining their opposition to the St John’s site.

Other issues have also been flagged by residents. A recent water cycle study, that assessed the efficacy of the district’s sewerage system and its ability to take on waste from more homes, has raised concerns as it suggests some treatment plants are at or near capacity, and at present would exceed capacity if more homes are added to the system without upgrades occurring.

In spite of vocal opposition, though, Exmo_20 has remained in the local plan.

The district council is trying to find locations for around 21,000 homes, and if it diluted or even removed the Exmo_20 site, it would have to find other places in the district to accommodate them.

There’s also further pressure in relation to government timelines; East Devon District Council is trying to ensure its local plan is submitted within a certain timeframe, because if it misses that deadline, then it might have to build a further 5,000 homes – taking it to 26,000 over the life of the plan.

“Hitting those higher housing figures would be extremely challenging,” Ed Freeman, assistant director for planning strategy and development management at East Devon District Council, has said.

“We don’t have a solution as to how we would hit those and so that’s important to understand.”

Frustration over cancelled Exeter elections

Other councils including Devon County Council and Teignbridge District Council have stepped up since Exeter announced its decision to offer help with running the 2026 elections if needed.

But will Cllr “Turkey” Bialyk take these offers, or double down on his plotting for Exeter to “go it alone” (spin to cover his hostile takeover bid for big slices of neighbouring districts)?

Is he becoming another “LINO”, leader in name only? – Owl

Opponents unite to demand Exeter elections

Guy Henderson, local democracy reporter www.radioexe.co.uk

Parties at opposite ends of the political spectrum have united in Exeter in a bid to overturn a decision to scrap the city’s 2026 council elections.

Earlier this week members of the city council’s ruling Labour group backed a move to get their leader Phil Bialyk (Exwick) to write to the government explaining his view that the polls should be called off.

A lengthy city council meeting heard that by not having the proposed elections for 13 seats on the council – eight of them Labour seats – the city would save a quarter of a million pounds and free up officers to prepare for local government reorganisation (LGR).

But furious opposition councillors – Greens, Liberal Democrats, Conservatives, Independents and Reform UK – said the move was undemocratic and denied the people of Exeter their right to elect their councillors.

Some also said the Labour group was ‘running scared’ of the elections, having done badly in the Devon County Council polls last year.

Leader of the Green group, Cllr Diana Moore (St Davids), said: “There must be something very wrong with the Labour leadership that opposition groups holding such a wide spectrum of views and political differences can unite to speak out against this unjustified assault on democracy in Exeter.”

The joint letter says the opposition parties have ‘low confidence’ that Cllr Bialyk will adequately express their views in his letter to local government minister Alison McGovern.

It goes on: “We have never once, since the wheels of LGR were set in motion, been presented with a single report to suggest that Exeter City Council lacked the resources to deliver both the May 2026 elections and a comprehensive LGR programme.

“The decision by the leader to ask for a postponement is, in our view, not evidence based and appears to place the interests of the Labour Party above the need for the council going forward to have a democratic mandate.

“Residents in Exeter expect to be able to vote every year – that’s the way our system works. So annual elections are a right, not a privilege, for our residents. The whole episode is a disgraceful disregard of democracy.”

Other councils including Devon County Council and Teignbridge District Council have stepped up since Exeter announced its decision to offer help with running the 2026 elections if needed.

As part of the opposition’s joint letter Conservative leader Cllr Peter Holland (St Loyes) said: “There are no compelling reasons – at this time – as to why the elections should be cancelled. It is my view, which is shared by the wider Conservative group here in the city, that it is morally and ethically wrong to cancel what are residents’ democratic rights to vote on a four-year cycle – outside of a national emergency such as war or a pandemic.”

“Mother of the House” Cllr Elieen Wragg – one of the Exmouth evacuees

“From the first knock on the door to alert us to the dangers, to the reception at the sports centre, the professional precision of all the agencies working together proved to be a textbook exemplar of how emergencies should be managed.

“It was truly inspiring to see the town, district and county councils working closely to ensure that there was calm reassurance and concern for the welfare of everyone.” – Cllr Wragg

How Exmouth bomb evacuees rallied together with fish and chips, wine and ‘holiday’ vibes

They had to sleep at a leisure centre but spirits were high

Molly Seaman and Shannon Brown Senior Reporter www.devonlive.com/

Officials spent the morning packing up the camping beds and tea mugs at the LED in Exmouth as the last of the bomb evacuees were allowed to return home.

It sounds like the start of a war-time novel but it was the reality for the thousands of residents evacuated from their homes when a 250kg bomb was found during dredging in Exmouth Marina on Wednesday, January 13.

The explosive was taken out to sea in the early hours of Friday morning (January 16) and detonated at around 8.12am. The 5,500 people evacuated are able to return to their homes and life is continuing as normal.

Businesses have been allowed to reopen along the waterfront today and children were able to return to their schools.

Despite the fear and worry felt by Exmouth residents, with one woman comparing it to coronavirus lockdown as the streets fell quiet, some found ways to lighten the atmosphere and brighten each other’s days.

In particular, praise has been piled on the LED leisure centre, which became a hub for residents with nowhere else to go, and housed around 120 people on Wednesday night.

Residents Lou and Sue, and their neighbour Gail, were evacuated from their homes and stayed at the LED while the cordon was in place.

Speaking about last night in the LED, Lou told the BBC: “Everybody’s been smiley faced, we’ve all enjoyed it. We bought a couple of bottles of wine last night and we’ve had fish and chips. I thought I was on holiday.”

A ‘party atmosphere’ was described on Thursday night, despite there only being around 20 people left in the temporary accommodation. Biscuits and chocolate were reportedly shared round, and people were chatting late into the night.

Lou continued in an interview with BBC Radio Devon: “We decided to stay in our own houses the first night, and then yesterday they came and said that [the risk] had gone up to a category 3, and we really must leave our houses.

“So with a struggle, we did leave our house because Gail said she was coming out as well and I don’t regret it for one minute, it’s been absolutely fantastic in here. I wasn’t going to leave but Sue persuaded me because she started crying, but I’m quite stubborn, but I know being ex-forces, I should have gone right away, but I didn’t.

“But it was brilliant, honestly, here, from the top to the bottom, they’ve been absolutely fantastic. They’ve treated us like gold.

“Anybody tells me that we’ve lost our spirit in this country, which I did believe, I think we’ve got it back, definitely, because I would rate last night as everybody coming together and smiling, having a laugh, having a joke. It was great.”

Several people said their experience put into context their night or two away compared to the prolonged ordeal people faced in past wartimes or during the current conflicts elsewhere in the world.

Sue added: “We’re lucky just to have [only] spent a night away. Those poor people have got nothing.”

Exmouth councillor Eileen Wragg was also among those evacuated. She told DevonLive: “What could have been a chaotic situation turned out to be the opposite.

“From the first knock on the door to alert us to the dangers, to the reception at the sports centre, the professional precision of all the agencies working together proved to be a textbook exemplar of how emergencies should be managed.

“It was truly inspiring to see the town, district and county councils working closely to ensure that there was calm reassurance and concern for the welfare of everyone.”

She said their efforts brought calm to what could have been a “distressing predicament’ and also commended the “immense courage and bravery” of the bomb disposal team.

Cllr Wragg added: “We are hugely grateful to all the service agencies and multitude of willing volunteers who helped to bring this frightening episode to a peaceful conclusion, albeit with a big bang.”

Devon and Cornwall Police Assistant Chief Constable Nicki Leaper agreed there was a “real community spirit”.

She said: “I cannot thank residents of Exmouth enough. Their collective effort to get out of their homes was appreciated. We don’t take this lightly. We had to extend the cordon and I know how frustrating that can be. It’s people’s sanctuaries.

“The multi-agency partnership working over 72 hours, I’m so proud of all our partners. We are trained to do this.”

Councillor Paul Arnott, Deputy Leader of Devon County Council and Leader of East Devon District Council, said local Tesco branches also helped with deliveries of food and duvets. He praised all the organisations and volunteers, including the Red Cross and the town council, who helped to oversee the safe resolution of the incident.

Bomb gone – Exmouth evacuees return home – Cllr Paul Arnott speaks

As “Three Homes” Jenrick makes a comprehensively leaked defection to Reform, claiming Britain is “broken”, one of the biggest bombs dropped by the Luftwaffe in WW2 is safely taken from Exmouth Marina out to sea and detonated.

Council Leader Paul Arnott compliments everyone involved in the massive emergency task of dealing with the bomb and evacuating 2,500 properties.

The bomb is reported to have been one of the three largest used by the Luftwaffe at around 250Kg. Dredged out of the Marina (original dockyard) the bomb fusing mechanism had to be identified before a floatation collar could be attached. It was then lifted from the dredging barge, lowered into the sea on the 2am high tide, towed out to sea and detonated on the sea bed. Best video of the process can be found on ITVX.

Two and a half thousand properties had to be evacuated as the safety cordon was extended from 400 to 600 metres. The BBC reports, for example, that Emma Kessie, the manager of the LED leisure centre, used as the emergency evacuation centre in Exmouth, said about about 100 people stayed in the makeshift accommodation on Wednesday night and about 20 people on Thursday. The rest were found temporary accomodation.

Emma Kessie, worked a 20 hr shift on the first night and describes the scene in the leisure centre as follows:

“The people who were sleeping here or just sitting here for the day have been incredible and had such enthusiasm and positivity,” she said.

“We stayed up having teas and coffees, I was doing microwavable meals at three in the morning… it was just great, it was a great vibe.”

[NB Owl hates to say it but Google AI gives a fair summary of why East Devon Watch uses the nickname “Three Homes” for Robert Jenrick.]