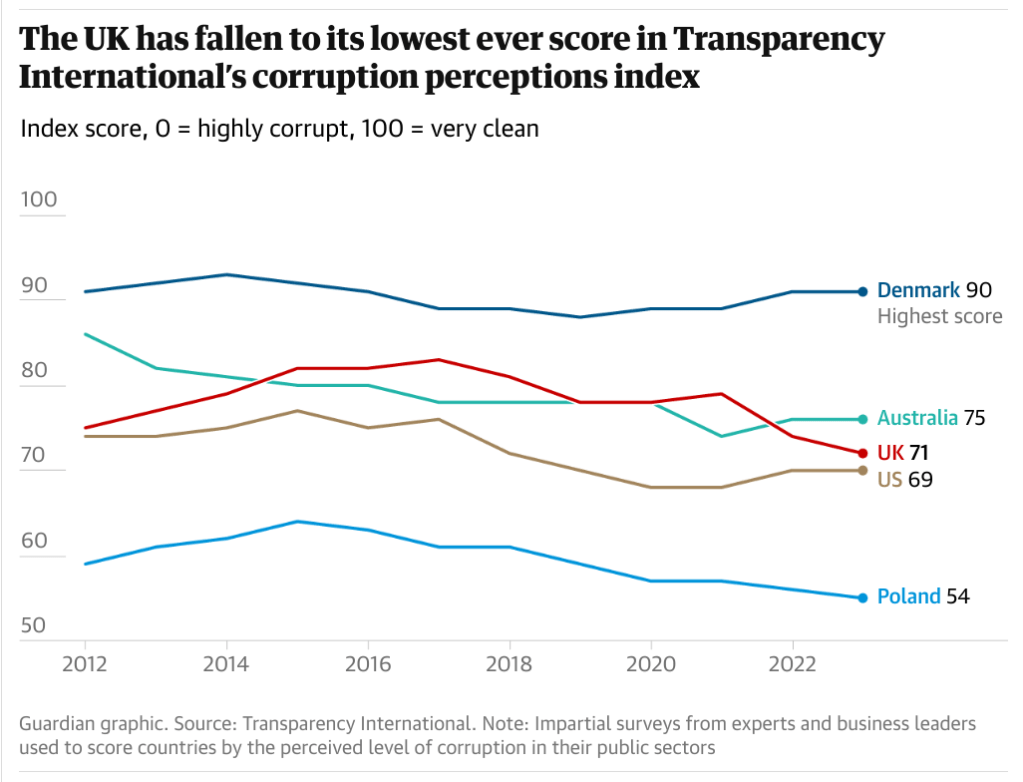

The UK has fallen to its lowest-ever position in Transparency International’s corruption perceptions index, which ranks countries by experts’ views of possible corruption in public services.

Rupert Neate www.theguardian.com

The UK fell from 18th (out of 181 countries) in 2022 to 20th in 2023, its lowest position since the research was revamped in 2012. It means that, according to the research, Britain is seen as more corrupt than Uruguay and Hong Kong.

The lower ranking coincides with concerns about possible corruption in the awarding of PPE contracts during the pandemic, according to the research published on Tuesday and based on “impartial surveys from experts and business leaders”. The UK was ranked at between the eighth and 11th most transparent country in the world between 2012 and 2021. However, it fell to 18th in 2022, and then joint-20th in 2023.

Daniel Bruce, the chief executive of Transparency International UK, said the findings should act as “a wake-up call for government”.

“The continued fall in the UK’s score shows a country heading in the wrong direction. It’s clear that business leaders and other experts are more concerned than ever about political corruption and the abuse of public office in the UK,” Bruce said.

“We need urgent action from ministers – not just words – to restore much-needed confidence in the integrity of political and public life.”

The total corruption perceptions index score awarded to the UK was 71 out of 100 (where zero means a country is perceived as highly corrupt and to 100 means it is perceived as very clean). It is the lowest the UK has ever scored on the index, and a drop of two points on 2022 and nine on 2018. The UK has experienced the biggest five-year decline of any western European country, according to the research.

The score is based on data from eight independent sources, including the Economist Intelligence Unit and the World Economic Forum. “All surveyed experts and business executives for their views on abuses of public office for private gain and bribery in the UK,” Transparency International said.

The anti-corruption charity said the scandal around the awarding of PPE contracts during the pandemic and concern that “both the UK government’s anti-corruption champion and independent advisor on ministerial interests [had] resigned”.

It added: “The data shows that while perceptions of bribery generally are improving, there are growing concerns over cronyism and patronage in politics, and its effect on the management of public funds.”

Denmark is ranked as the least corrupt, followed by Finland and New Zealand. South Sudan, Syria, Venezuela and Somalia are at the bottom of the rankings, meaning they are seen as the most corrupt. The US is 24th.