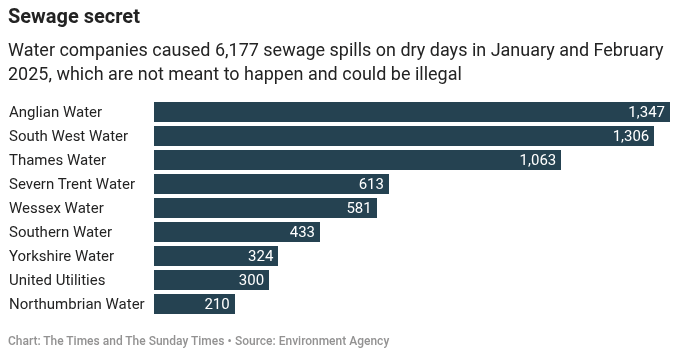

New data show Anglian Water was the worst offender, followed by South West Water and the crisis-hit Thames Water.

Adam Vaughan www.thetimes.com

England’s water companies are causing more than 100 potentially illegal raw sewage spills a day into rivers and seas, far more than previously thought, The Times can reveal.

New data, which suggests a previously unknown level of widespread breaches of the law, shows Anglian Water was the worst offender, followed by South West Water and the crisis-hit Thames Water.

The potentially illegal nature of many of the spills raises the prospect of a wave of prosecutions and potential multimillion-pound fines for water firms. Regulators said the figures were “unacceptable” and they would not hesitate to take enforcement action against breaches of permits.

Raw sewage is legally permitted to pour into waterways from relief outfalls, known as storm overflows, on days of heavy rainfall. Those legal spills, which lasted a record 3.61 million hours last year, have sparked public outrage and targets from ministers to halve them.

However, they are not meant to happen on dry days, when the risk to swimmers and wildlife is greater because the pollution is not diluted by rainwater.

Companies have previously cast doubt on independent attempts to gauge the extent of such “dry day spills”, which experts said were likely to mostly be in breach of permits and illegal, with a few exceptions.

The previous best estimate was about 6,000 dry day spills in a year. However, the data shared with the Times shows that number in just two months.

“The massively high numbers of untreated sewage spills on days when we haven’t had exceptional rainfall is the canary in the mine — clear evidence that our sewage infrastructure and capacity has not kept pace with population growth, development and climate change over the last decades,” said Michelle Walker, the technical director of the Rivers Trust, a charity.

The Times, which obtained the data using transparency laws, can disclose there were 6,177 dry day spills by nine water companies across January and February. Anglian Water reported 1,347 dry day spills, followed by South West Water on 1,306 and Thames Water on 1,063. Northumbrian had the lowest figure, with 210.

The figures have come to light because since January the Environment Agency (EA) has required water firms to report dry day spills. It now classifies them as pollution incidents.

Much of Britain’s sewer system is based on the model chosen in the 19th century, of combining rainwater and sewage in the same pipes. During heavy rainfall, storm overflows can by design be used to stop sewage backing up into homes and businesses.

However, dry spills should not happen. Observers said the high frequency of day spills uncovered by The Times suggested companies had failed to keep sewers clear and had not invested enough in infrastructure to keep pace with population growth.

A dry day is defined by the EA as having no rainfall above 0.25mm on the day and the 24 hours beforehand. “Storm overflows should not spill on dry days,” the regulator has said.

The new figures are important because they are sourced directly from the water firms. Some companies have contested past efforts by the BBC to infer how many dry spills there were by cross-referencing stop-start times of sewage spills with weather data, claiming the methodology was flawed.

The agency is in the process of establishing how many of the 6,000-plus discharges were illegal. The regulator has said dry day spills could lead to prosecutions, written warnings and financial penalties for companies.

Alex Ford, a professor of biology at the University of Portsmouth, said the EA was likely to find a high level of illegality. “Most, if they occurred during dry spells, are illegal. They would still be potentially illegal if they were caused by delayed rising water tables and seepage into cracked pipes,” he said.

Experts said dry day spills were typically more devastating for people and the environment than those during exceptional rainfall.

“Definitely, dry weather spills are worse because of the lack of dilution in the river — so any pollutants or infectious pathogens will be more concentrated if someone were to swallow some of the water,” said Barbara Evans, a professor of public health engineering at the University of Leeds.

“In dry weather people may be using the rivers and beaches more, so there are more people who may then be exposed to the pollutants,” she added.

Most of the dry day spills are understood to be classed by the EA as category three pollution incidents, where one is the most severe and four the least. The reasons why dry day spills can occur include under-investment in pipes and treatment plants, blockages in sewers and groundwater infiltrating into pipes via cracks and other routes.

Some of the spills this year could have happened without permits being breached. For example, in a large catchment water may fall in one place and take more than a day to drain down to another area where the spill occurs.

However, campaigners said the scale was unacceptable. Giles Bristow, the chief executive of the charity Surfers Against Sewage, which uncovered early evidence of dry spills in 2022, said of the 6,177 spills: “It’s outrageous, unlawful, and a damning indictment of a water industry broken beyond repair.”

The group’s provisional data shows a total of 206,529 raw sewage spills during January and February, most of which will have been legally permitted. “It’s bad enough having to think twice on taking a dip after rain — to do so in dry weather is just downright ludicrous,” said Bristow.

An EA spokeswoman said: “The number of pollution spills happening in dry weather is unacceptable. We investigate every dry spill and our message to the industry is clear: we will not hesitate to take robust enforcement action where we identify serious breaches.”

A spokeswoman for the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs said: “Our root and branch reform will revolutionise the water industry through a record £104 billion investment.”

All of the companies were contacted, and none disputed the figures. Anglian Water said it is spending around £1 billion on storm overflows up to 2030. “We recognise that customers want us to take swift action to end storm overflow discharges. We intend to meet these expectations,” a spokesman said.

A South West Water spokeswoman said: “We are clear that storm overflows must only be used when absolutely necessary.” The firm note said it was trying to eliminate dry day spills caused by groundwater infiltration.

A spokesman for Water UK, the industry body, said: “No spill is ever acceptable. Water companies are working to end them as fast as possible by tripling investment. Over the next five years, companies will invest £12 billion to halve spills from storm overflows by 2030 including relining and sealing sewers to prevent groundwater infiltration — one of the main causes of dry day spills.”